The University of the Self #39

The Mind's Place & Using the Self as Archive

Before I begin the essay, I wanted to share a new piece of my asemic writing - this is a series of two pieces I made in July this year (2024). It’s title is ‘String Theory II’ and I love the way it spoke back to me as I was creating it of a nucleus of creativity, and the way such a nucleus can explode out into further constellations.

Content warning: this lyric essay discusses, in some places, loss, grief and ghosts.

i Self As Archive

In order to establish our unique writer’s voice and produce the kind of poetry we wish to write, we must first understand who we are. Is this realistic? Do we ever truly know ourselves? Our myriad selves?

When I think about place writing, I think about the mind as a place which is difficult for others to access — it feels like my most private place. My safest place. The most dangerous place. The deepest place, the hardest to know or map place, the place where I/we can become absolutely lost. Sometimes, I have hidden things inside it that I can no longer find. Sometimes, unexpected flotsam rolls in on its tide. Their are coastlines in clarity and there are hinterlands occluded by mist. Our minds are places filled with ghosts. I also think of the mind as a place which is difficult to navigate. It is a place of conflicts, I place I often feel I can’t fully access; a place where I can become lost, frightenend and frustrated; a place of questions; a place of both pleasant and unpleasant memories; a place in constant flux.

Our bodies are lands that I feel can often be more readily invaded. No matter what has happened to my outside self, I have found ways to retreat inside. Our minds are our last defence, though of course our minds can be and are invaded too — I think of the phrase ‘people get in your head’ often. Advertising, social media, work, family, health and stress gets into our heads. I wish I had a £ for every time I have been accused of ‘over thinking’, of ‘dwelling on things’ I’d be so rich I’d never have to worry about money again. Of course I think. The mind is a thinking place. Of course I dwell on things. The mind is a dwelling place. I think of this quote from John Milton’s Paradise Lost (Book I, Lines 221–270):

“The mind is its own place, and in it self

Can make a Heav’n of Hell, a Hell of Heav’n.”

Indeed it can.

People often say that ‘the mind is a lonely place’, though I do not know who originally coined this phrase. I think of this quote from Aldous Huxley:

“The more powerful and original a mind, the more it will incline towards the religion of solitude.”

I must clarify that using this quote does not mean that I believe myself to own a powerful mind, of that I am puffing myself up as some sort of genius. I think of this quote more as an articualtion of how thinking and learning can make me feel. Does thinking contribute to solitude? To loneliness? I do better when I am alone, that is for sure, though I often worry that I am failing to acknowledge or recognise ‘loneliness’. It is true that my thoughts, behaviours, “Hobbyhorses” (with many thanks to Laurence Sterne for the descriptor) and conversations have (especially as a child/teenager/young adult) left me vulnerable to teasing, bullying, nastiness and rejection.

The mind is a quiet place and at the same time, the mind can feel overwhelmed with noise. How does one deal with one’s mind? How does one process its constant information overload? Its thoughts, hopes and desires? This is a question I have often asked myself. I thought about libraries, and how each set of requirements is set out in its own area. What if you think of your mind as an archive the same? What if you use this archive to really get to know yourself?

Imagine all these shelves — row after row, section after section from floor to ceiling. The room that holds the shelves is so wide and so long it seems that you have become Self as Infinite. If you look far enough, you will see where the shelves, the roof, the floor and even the air inside the room converge. You see Self as Vanishing Point. Don’t worry — move towards it if you like. You won’t disappear. Your vanishing point will have moved further forward, is all.

On the shelves are an incalculable amount of files. This is the documentation of your life (so far). It proves you have been alive for this long. That you exist. That you have a past, a present and a future. Who is in charge of this archive, if not you? It is yours. You probably won’t remember many of the documents kept in it — after all, the archiving began when sperm touched egg. It started even before that, when Self as Egg was still unfertilised (see Gamete Digression here).

You do an internet search to find out how long you were alive before the addition of a sperm (note to Future Self: you are definitely going to write a poem about this at some point). Twelve to twenty four hours was the precious early time when you were truly alone, when you were Self as Untouched. You began as a nucleus and some chromosomes (discover by happy accident that hens lay their eggs according to the light. This is superb information. Paste it for later, into the scrapbook of your head. You are definitely going to write a poem about this at some point. I will write my thoughts on Tangential Research lower down on this post).

This early part of your archive might only appear as small indications of light. How this might be interpreted will require experiment. Your files move on into the weeks, months, years. The streets you lived on, the schools you might have been to, the people that you might have known. The rabbit called Betty in the bright blue hutch, the flowers you picked for someone you love. All the ages and stages of you are stored here. I will say that this is a bit of a life’s work in itself. Do we have time to archive shelve everything that has happened to us? Possibly not. But this is a great system of sorting out specific series of memories, thoughts, research, inspirations and experiences.

Try mapping the sections out by hanging imaginary signs above them and label the sections as a library might. Don’t worry about naming every section now. Some sections are still waiting to reveal themselves to you. Some you may not yet be ready to name. Some are earmarked for the future. Some, like quick fish, seem to difficult to catch hold of. You might like to write these shelves down in notebooks — it really helps me organise the jumbles in my brain.

Imagine all this information stored neatly on shelves, waiting for you to pick them up whenever you have need. This is where you keep words and ideas that interest you, words that you have seen or felt, words that come from experiences you have had. You might, for example, keep a section called ‘The Notyou’—this is where you list things that, quite literally, are not you. Things like nature, animals and auotomobiles, plant pots and refrigerators. The Notyou—the sign blooms like an orchid from the wall. The air around here is a complex web of sensory information.

You might break down your Notyou categories into further subsections, something like this, for example (or completely differently, in a way that suits unique you):

The Notyou — Nature Made. In this section, you keep weather, flora, fauna, stone. There are many files. Some are called:

smell the ocean ǀ investigate the grass ǀ wildflowers ǀ feeling of warm sand

most beloved trees ǀ a waterfall ǀ fields ǀ tundra ǀ glacier ǀ mountain rocks ǀ cliff ǀ desert ǀ rainforest ǀ savanna ǀ wetland ǀ ravine

Others are called:

ground-creatures ǀ sky-creatures ǀ of the water realm ǀ tree-creatures

hypogean magnificence ǀ crawling creatures ǀ microscopic unseen

incredible creature-myth ǀ blaze of angels ǀ hinterland of ghosts

These files pend like cherries from a bough, tempting, reachable.

The Notyou — Human Made. In this section, you keep metal, plastic, cooking, clothes, art, methods of communication etc. There are many files. Some are called:

entity as house ǀ incredible machines ǀ existence/robot ǀ automaton ens

artificial flight ǀ drystone wall ǀ vehicle corporeality ǀ tarmac vein ǀ coil pot

carving ǀ oil paint ǀ taco ǀ wheel ǀ harness ǀ plough ǀ paper

There are many, many more than these but the above will give you some idea of the range. The above shelves are unspecific, as I wanted to use them as a broad example. What if, say, you were working about a poem about time? You could narrow down your Notyou shelving to include only pertinent details thus:

clock ǀ hand ǀ hour ǀ second ǀ minute ǀ key ǀ mantlepiece ǀ dial ǀ face

alarm ǀ quarters ǀ mechanism ǀ glass ǀ pendulum ǀ tick ǀ tock ǀ chime

Cataloguing yourself can be much more difficult— use index cards if it helps, or go microfilm if you know how to operate such high-tech stuff. Personally, having just considered a catalogue, I find I love the idea of boxes of cards, well-thumbed, hand-written, tactile, interactive, brushed with your DNA, intensely personal. This may help you pilot this complicated space. You are endlessly complex. Try shelving yourself small section by small section. For example:

The You — Clothes.

I do not like tight waistbands ǀ I do not like underwired bras ǀ I love soft feeling fabric

when I am most stressed I sleep in a woolly hat ǀ I like big fancy collars ǀ I do not like tights that feel too small but I hate tights that fall down ǀ I do not like the feeling that my shoes are slippery ǀ I like to use the edges of hems to stim-stroke ǀ I love the way socks hold my feet ǀ my wedding dress had layers of frill on it like a waterfall ǀ beads are fascinating

Negotiating emotion using this method is a lot more difficult and must be handled with great care, as it can be triggering. Keep yourself safe when you search. Making these shelves using your private feelings is just for you, so I hope you understand when I do not offer one of mine as an example.

Beware the section lit by a low-watt, flickering sign. It swings loose on its hanger. Its wires creep and spark like livid snakes. Here, I keep the shelf for SHAME. Motes cling the weak light. The uneven path continues on to PAIN. Go easy, same as you would if you had to enter deep water. These sections require cautious navigation.

There is complicated terrain here — spike and fissure, quag and storm. In your quest to reclaim/react to/research your archive, you may forget to care for yourself. The door into the archive is never closed. Tell yourself any time you want to, you can leave.

ii Tangential Research: Using the Divagation Tree and its Alternative Paths

Following on from your archive shelves: how might these words / phrases from your shelves be further developed upon? The Divagation Tree is an interesting way of kindling manifold paths. It will demonstrate to you the limitless capacity of words and the myriad directions that they might take. The tree is useful in encouraging each separate word, or small grouping of words to ‘speak onwards’. Imagine an idea or word growing along each branch of the tree. Relax into the word. Give yourself over to the word and free-write your way as far as you can from branch to twig, to smallest splinter. Do not question what comes to you during this process. As with all writing, the questioning, further writing and editing comes into play much later.

Each tree you grow will be unique. Grow many. Grow your mind into a forest.

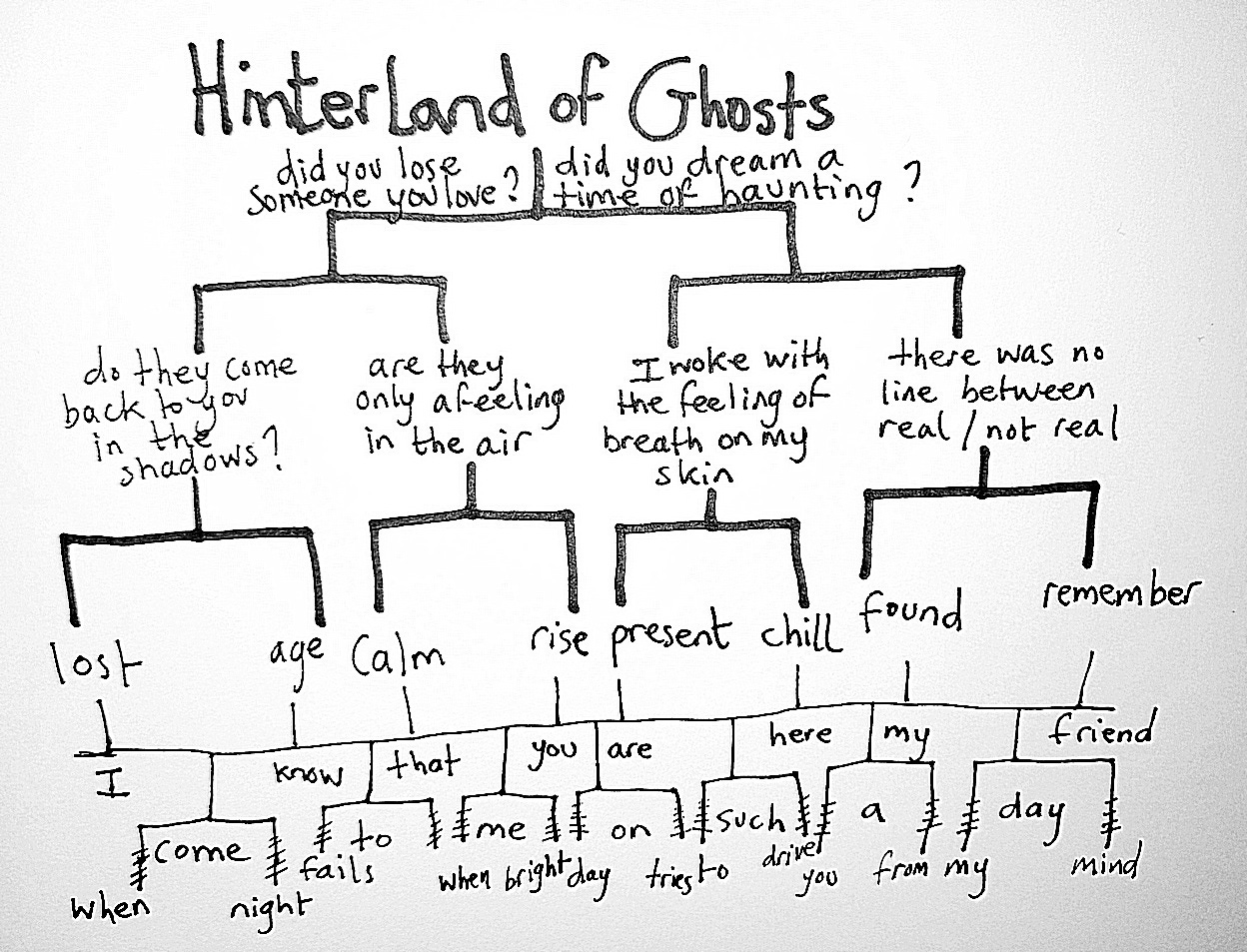

Example of a Divagation Tree made using a phrase from on of my Notyou — Nature Made shelves above:

Image description: This is a diagram that has the title ‘Hinterland of Ghosts’ at the top of the white page. Underneath the title, lines branch out, as a stylised tree. The first branch has the words ‘did you lose someone you love?’ and ‘did you dream a time of haunting?’ written on it. Four more branches grow from the one above. Written under them are ‘do they come back to you in the shadows?’, ‘are they only a feeling in the air?’, ‘I woke with the feeling of breath on my skin’ and ‘there was no line between real/not real’. From there, eight branches appear. Written under them are ‘lost’, ‘age’, ‘calm’, ‘rise’, ‘present’, ‘chill’, ‘found’, ‘remember’. From there, a branch appears with the line ‘I know that you are here my friend’ written underneath it. From there, more branches appear with the line ‘come to me on such a day’ written underneath it. From there, the final branches with the line ‘when night fails when bright day tries to drive you from my mind’ written underneath it.

What you know has the potential to be inexhaustible.

Using the above diagram as a starting point, I grew my tree in more detail.

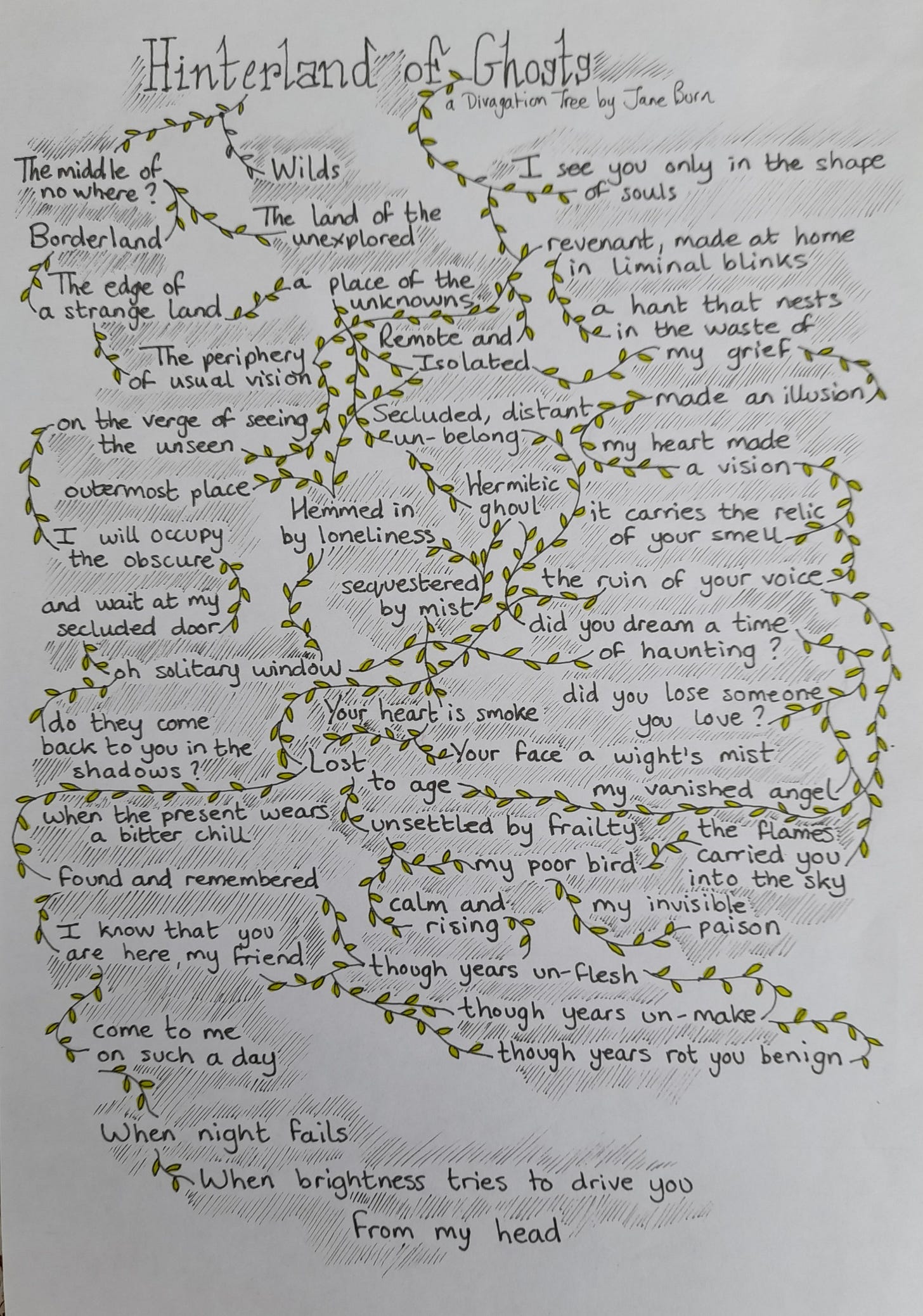

Extension of the Divagation Tree:

Image description: This is a diagram that has the title ‘Hinterland of Ghosts’ at the top of the white page. Underneath the title, lines branch out, as a stylised tree, with organic lines decorated with small green leaves. Lines of words grow from the branches and fall like leaves down the page. The words are as follows:

The middle of nowhere

Borderland

The land of the unexplored

The edge of a strange land

Place of the unknowns

I see you only in the shape of souls

the periphery of usual vision

remote and isolated

Revenant, made at home of liminal blinks

a hant that nests in the waste of my grief

On the verge of seeing the unseen

Secluded, distant un-belong

made an illusion

My heart made a vision

Outermost place

hemmed in by loneliness

hermitic ghoul

it carries the relic of your smell

the ruin of your voice

I will occupy the obscure and wait at my secluded door

sequestered by mist

Did you dream a time of haunting?

Oh solitary window

Your heart is smoke

did you lose someone you love?

Do they come back to you in the shadows?

Lost to age

your face a wight’s mist

my vanished angel

When the present wears a bitter chill

unsettled by frailty

my poor bird

the flames carried you into the sky

Found and remembered

calm and rising

my invisible paison

I know that you are here, my friend

though years un-flesh

though years un-make

though years rot you benign

Come to me on such a day

When night fails

When brightness tries to drive you

from my head

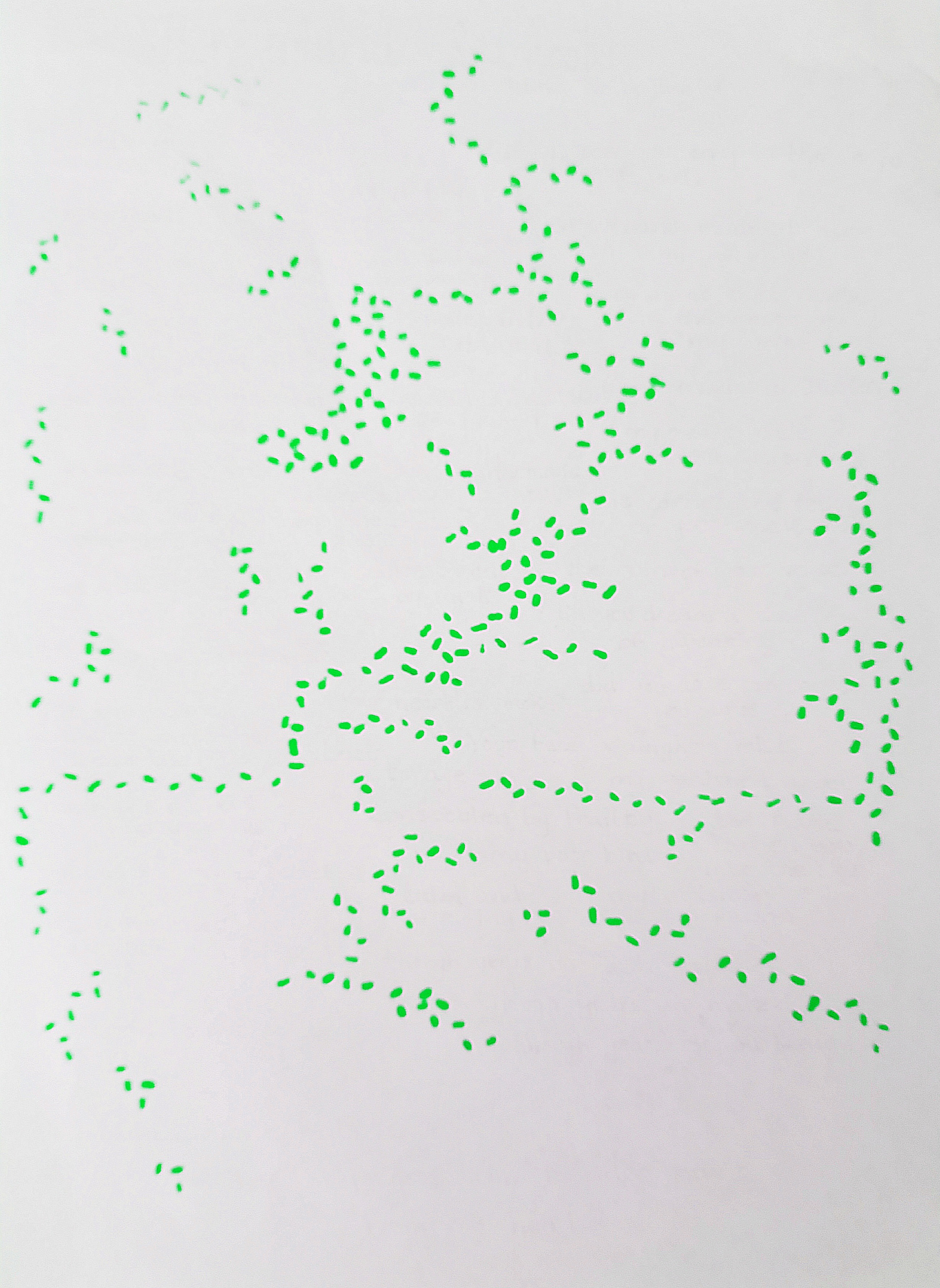

Divagation Tree Extension: where the whole is distilled to its pattern of leaves.

I asked myself, is this still a poem?

I would say wholeheartedly yes, especially if you take into account the history of redaction / erasure in poetry—I think here of works like Poem by Man Ray, 1924 —how poems like this are poems that can

“be understood by all…a universal language. You don’t even have to know how to read to read it!” (Young, D. 2010, p.110)

This Divagation Tree Extension is more than a poem. It is the fingerprints, the spoor of the poem. I think this might be my first asemic work — or perhaps it is the forerunner of my interest in asemic work. When I began these experiments, I never dreamed I would finish on the image below. The journeys writing can take you one never cease to amaze me.

Sources

Young, Dean. THE ART OF RECKLESSNESS. Graywolf Press, 2010.

Please consider helping me to keep on sharing my articles with you…

I hope you enjoyed reading my latest article. Thank you so much for spending some time here with me. Times are tough, but if you feel like supporting a struggling writer so that she can continue being able to write, (every tiny bit helps) you can do so below…

I have currently left my Substack free, but if anyone should feel like sending me a tip (although there is no pressure to do so) in exchange for my tips, you can ‘buy me a coffee’ here . Every little bit makes a big difference. Or please do subscribe, which you can do either as paid or free. Many thanks.

I must add the usual disclaimer here: I am not sponsored or paid by any of the websites I link to (I do this in an attempt to help others find information, and I may or may not agree/disagree with any/some of the content) — sharing does not immediately equal endorsment. I also hope I haven’t written anyting that might offend anyone. I try very hard to be as considerate and kind as possible.